“Oh Well (2)” courtesy of Lydia Komatsu

So many books, so little time. Pete Molin put up a wonderful review of Luke Mogelson’s These Heroic, Happy Dead | Time Now that I highly recommend.

“Oh Well (2)” courtesy of Lydia Komatsu

So many books, so little time. Pete Molin put up a wonderful review of Luke Mogelson’s These Heroic, Happy Dead | Time Now that I highly recommend.

The other night, I had the chance to sit at a bar in Anchorage with Brian Castner and discuss a few things I’d mentioned in my blog post on All the Ways We Kill and Die. One of the things we talked about was the idea of the veteran writer who works both in journalism and the literary world; and how short the list really is. But one of the guys who we agreed could write great essays in addition to reportage was Colby Buzzell.

The other night, I had the chance to sit at a bar in Anchorage with Brian Castner and discuss a few things I’d mentioned in my blog post on All the Ways We Kill and Die. One of the things we talked about was the idea of the veteran writer who works both in journalism and the literary world; and how short the list really is. But one of the guys who we agreed could write great essays in addition to reportage was Colby Buzzell.

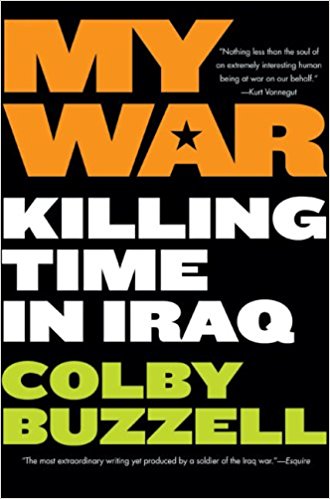

I’d have to check in with Pete Molin over at Time Now (he shared his far-more-intelligent-thoughts on My War here) but I believe that Buzzell’s My War: Killing Time in Iraq was one of the first, if not THE first, literary memoir to emerge from Iraq. First published in October of 2005, the flash-to-bang on the memoir’s production was incredibly tight: Buzzell deployed to Iraq in 2003 with the Army, and came home in 2004. Which means what I’d estimate to have been less than a year to write and finish the book. Coincidentally, Buzzell deployed at roughly the same time as Brian Turner (My Life as a Foreign Country), who was also stationed at Ft Lewis, WA. Two remarkable writers in the same neighborhood: I have to wonder if their paths crossed at some point.

It’s hard to remember now, but blogging was kind of a new thing back then. Blogs were springing up all across the web, and being heralded as a kind of democratic approach to journalism. And those deployed to Iraq were taking advantage of the medium for a variety of purposes as well. I can recall coming across one while I was in Iraq, established by a guy I knew deployed at the same time as me, as a way of keeping his family updated. Colby Buzzell, on the other hand, was by all accounts looking for a way to pass the time. So he established an anonymous blog that ended up going viral. He’s still got the original blog posts up at Blogspot if you want to check them out.

I probably read the book within a year of its release and its raw prose blew me away. Unlike the repetitive autobiographies of trigger-pullers and generals, it was clear that Buzzell was grappling with the larger story of what it all meant. That last sentence is important to me in terms of taxonomy: for the most part, I don’t read non-literary war memoirs. If all you’ve got in your story is a bunch of things that happened to you, Godspeed. Those stories are important, and I’m glad they’re available. They are, or can be, art. A literary memoir, however, is at least trying to be Art, and does so by chasing the meaning of an experience.

That right there is the lesson of My War for war memoirists (and maybe even any author in general.) You need to be able to answer the question, “what’s this all about?” And my gut feeling is that answer can’t be, “it’s about me going to war,” unless you’ve got one hell of an exciting or unique perspective. There needs to be some kind of through-line. Slaughterhouse Five is certainly a war novel. But above that, it is about the moral complicity and guilt Vonnegut felt as a result of what he experienced during WWII.

My War answers the question adequately enough — and it didn’t hurt that Buzzell’s voice was fresh and unique. But most importantly, there’s enough connective tissue in there to take it beyond a disparate collection of things that happened and into literary territory.

The first time I spoke with an agent, he asked about my memoir manuscript.

“It’s a lot like Jarhead,” I said.

He shook his head. “Every one says that about their war memoir. Don’t say that.”

I don’t use the comparison much anymore, but it’s always on the back of my mind. Probably because Jarhead essentially broke the mold for literary war memoir. Others might be quick to raise their hand and point at Tim O’ Brien’s little-known Vietnam memoir, If I Die in a Combat Zone, as the genre-breaking prototype for contemporary war memoir. And I agree: it was the first to attempt essay collection as memoir. But it was still half-baked in my opinion. I don’t know enough, but my gut tells me it had something to do with not having any contemporaries from which to draw inspiration. It’s usually the first question I ask an author regarding their books: what were you reading when you wrote this book? In O’Brien’s day, creative nonfiction and its stepchild, literary memoir, was still busy being born. There were no Boys of My Youth (Jo Ann Beard) or even In Pharoah’s Army (Wolff, which pushes the form along) from which to draw inspiration. By way of example, consider contemporaries Phil Caputo’s A Rumor of War and Herr’s Dispatches: Caputo’s is very much a chronological story, while Herr’s is wild and all over the place. In the time in which O’Brien wrote his war memoir, writers are still stuck on the idea that memoir translates better as fiction (interesting note, Jo Ann Beard’s story “The Fourth State of Matter”, which gave birth to Boys of My Youth, originally ran in the The New Yorker as short story – it was the only way they could fit that brilliant piece within their strictures of genre.) Point being: O’Brien’s series of linked, memoirist essays, still feels disjointed enough to feel like memoir, but not quite.

Twenty five-odd years later, enter Swofford. Creative nonfiction is booming, memoir is selling like hotcakes. There are plenty of examples to follow, as noted above. And what’s more, Swofford is studying at the most prestigious MFA program in the country, The Iowa Writer’s Workshop, where he’s surely being exposed to a litany of cutting-edge nonfiction.

Jarhead is Swofford’s account of his time as a Marine during Operation Desert Storm, but the book is much larger than that. Each chapter functions like a stand-alone essay, linked by experience, voice, and easy transition in order to allow the narrator to dwell on one particular aspect of that time of his life without regard for chronology or the expectation that one should begin at the beginning and end at the end.

It’s “THE war memoir,” according to the agent I spoke to that day: the one all other contemporary war memoirs are measured against. I’ve read a lot of them — nearly all of the literary ones — and the book deserves the honor it gets. It sold well, its release date concurrent with the onset of Operation Iraqi Freedom, and what’s more, it’s a remarkable telling of a screwed up human on the edge of the empire that teeters between raw emotion and gut-piercingly beautiful prose. The balance is remarkable, really. So good, some say, that Swofford will have a hard time surpassing it.

I try not to think of the comparisons too much, especially since I’m still working my way through the second draft of my own manuscript. But I’m always keen on drawing at least one lesson from each book I read. A lesson I can explicitly apply in my own work. And I’m not ashamed to say that Jarhead is my standard when it comes to translating war experience into an essay collection as memoir. It taught me a strong lesson in the idea that an essay can disguise itself as chapter, and that because a reader will recognize the comforting and familiar shape of such a thing, it offers a naturally occurring structure for the full exploration of an idea, thought, or theme.