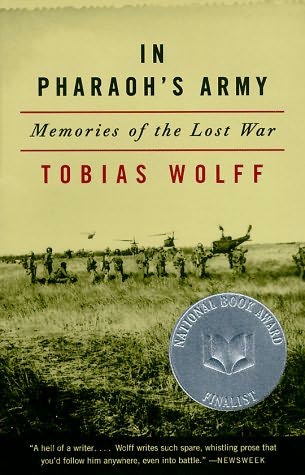

You don’t have to get too far into In Pharoah’s Army to realize this isn’t your average Vietnam kill pulp. The memoir of Wolff’s time as an Army Special Forces officer in Vietnam explores all the nooks and crannies of the wartime experience that have nothing to do with combat, saving the kinetic stuff for a kind of sort brief, violent salve. It’s a remarkable book, the first war memoir I read before I knew “war memoir” was a thing.

You don’t have to get too far into In Pharoah’s Army to realize this isn’t your average Vietnam kill pulp. The memoir of Wolff’s time as an Army Special Forces officer in Vietnam explores all the nooks and crannies of the wartime experience that have nothing to do with combat, saving the kinetic stuff for a kind of sort brief, violent salve. It’s a remarkable book, the first war memoir I read before I knew “war memoir” was a thing.

Anyone who knows Wolff’s other work (say, The Barracks Thief or This Boy’s Life) can attest to his ability to use self-deprecation as a means of parsing the world. But what I found so entertaining about In Pharoah’s Army was the construction of a narrator who was lacking “the courage to admit [his] incompetence…was ready to be killed, even, perhaps, get others killed, to avoid that humiliation.” Wolff’s narrator takes us on a kind of hapless, malingering, and (of course) tragic journey through the Vietnam experience. He’s the antithesis of both the stereotype we apply to today’s Special Forces; he’s also the polar opposite of any kind of war lit hero archetype. It’s fascinating, because unlike Catch-22‘s Yossarian, whose nihilism isolates the character, Wolff’s narrator is quite accessible.

I suppose it might be a little disingenuous to some to compare fictional characters with nonfiction, but we all would do well to recall that any literary character found in either genre is at best, some kind of imagined thing. Any interesting character anyway…

I think it’s fair to call the memoir “essayistic,” with chapters that seem capable of standing as independent stories. The book itself is broken into three large sections that align with pre-, during-, and post-Tet Offensive. Of course, the prose is deft, the narration restrained, and the narrative arcs are controlled. It’s Wolff in the tradition of This Boy’s Life. But now the boy has gone to war.

The last thing I want to mention in this short post is time. And not in terms of how long it took me to read the book, but how much time elapsed between Wolff’s deployment to Vietnam in 1968, and when he published in 1994. 26 years is a lot of time to sit on this kind of story. In the past decade, war writers of my generation are producing their war memoirs within five years of the experience. I don’t know if this is due to market forces, sharp agents, or editors with chops, but it’s worth noting. They’re putting out memoirs, and not just kill pulp, but real-deal-literature-that-kids-are-gonna-read-in-high-school: it’s coming hard on the heels of what are typically single deployments by non-career servicemen and women.

I don’t bring it up to say that we should be waiting 20+ years to tell our stories. I simply highlight it because it’s a perfect reminder that only the author can say when the story is ready for primetime. Some books probably needed to marinate a bit longer. Others, a bit less. And some, like this one, are just right after waiting a quarter-century’s worth of ripening.